Energy Department Scans Documents to Boost Productivity

In the past few years, however, some DOE offices began converting paper to electronic files on a regular basis to simplify workflow, improve accuracy and better comply with regulations.

DOE’s document imaging relies on Fujitsu scanners, Freedman says, because of the quality of the scanned image, the reliability and support of the scanner hardware and integration with the Kofax VRS scanning interface.

“The DOE gets an array of paper document types and contents that need special, personal attention to ensure the electronic scans properly reproduce the original scanned page,” he explains.

VRS enables the scanner and its software to automatically adjust the quality of the scan to meet a targeted level of brightness and contrast. If a page does not meet the standard, the scanning process can be stopped and the quality of the scan adjusted in real time.

Internal customers are thrilled with the electronic content, Freedman says.

“Instead of having a roomful of filing cabinets with inaccessible documents stored by various organizational methods, their content is virtually instantly locatable through basic filename and file content searches,” he says.

“When many customers first work with searchable electronic files instead of hard-to-access paper documents, they contact the group to say how much easier their job is,” he adds.

Agencies Need to Plan Before They Scan

Besides providing records storage, NARA’s Federal Records Centers also offer consulting and digital imaging services to create scanned files of an agency’s analog records. Agencies often turn to FRCs for help because they don’t have the staff to handle scanning a large volume of documents, but Miller says the bigger challenge of any scanning project is getting organized and understanding the tools before scanning.

“You must understand those records’ complexities to establish requirements and ensure quality control,” he explains. “Before thinking about technical requirements, there is a lot of legwork that has to be done. If records haven’t been managed well over their lifecycle, we are not going to be very successful in a scanning project.”

Michael Wharrie, assistant director of the FRC in Riverside, Calif., which serves federal agencies in Arizona, Southern California and parts of Nevada, once created electronic versions of aircraft blueprints from 1937. The Federal Aviation Administration wanted to be able to look at drawings quickly without having to pull a 20-foot-long diagram out of a drawer.

“We didn’t realize it, but in those days, when they did engineering drawings, they drew them to scale,” Wharrie says. “These blueprints were folded nicely in a box, but when we opened them up, they kept getting bigger and bigger.”

The blueprint of the Ryan S-C 150 prototype wing was as big as the wing itself — nearly 38 feet long — yet still in surprisingly good condition. Although the FRC had some scanners to handle large documents, it did not have anything that could handle a drawing that big, he says: “We had to scan it in sections.”

VIDEO: See how USCIS and SBA evolved their websites with emerging technology!

The Library of Congress Preserves the Irreplaceable

The agency with the most challenging decisions is the Library of Congress, which has been collecting documents and images for more than 200 years and has been digitizing for about 20.

Prioritizing digitization projects spans multiple specializations within the library, from identification of candidate materials for digitizing to online presentation and archival storage of the digitized files, says Thomas Rieger, manager of digitization services.

Sometimes advanced imaging techniques can reveal unseen aspects of faded documents. “A wonderful example of this was the discovery that the original draft of the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson considered us to be ‘subjects,’ not ‘citizens.’ You cannot see this visually,” Rieger says. “Now we have the capability to offer this text in a searchable format using optical character recognition technologies.”

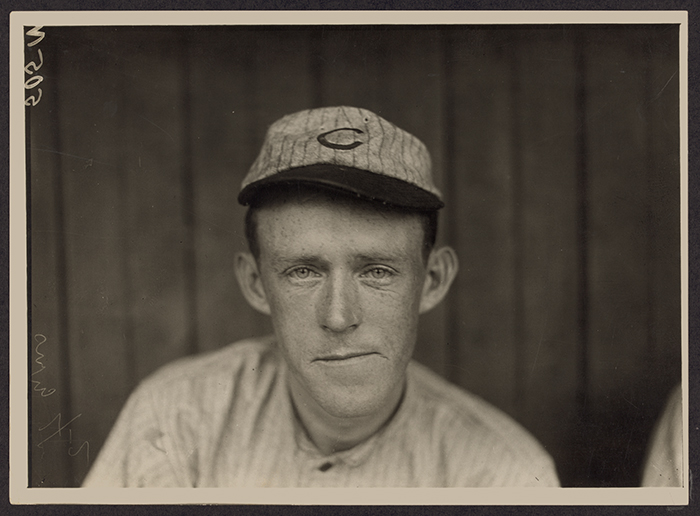

Chicago Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers, part of the famed Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance double play combo, stares into a camera in 1910. The photo is among the petabytes of digital data stored at the Library of Congress. Source: Library of Congress

For documents, the library uses ultrahigh-end, medium-format digital cameras, with outstanding lenses and best-in-class lighting and copy stands, Rieger says. For large materials, the library has floor-mounted scanners that scan huge originals in one pass.

“High-volume scanning is an interesting application, where the best solutions may not be the obvious ones,” Rieger explains. For instance, the scanner with the highest purchase price may lead to the lowest cost per image capture and the highest productivity, he says.

MORE FROM FEDTECH: See how agencies are moving toward digital records.

Digital Scanning Technology Keeps Improving

Scanning photographic materials has its own special requirements, and stretches the capabilities of current technology to capture all the detail that is actually in the images, Rieger adds. In addition, the library scans so much material that most commercial products, while exceptional for regular use, can’t handle the workload.

“We use custom-built film scanners to make this effort possible, and are now digitizing the library’s vast photographic negative collections using these systems,” he says.

Every few years, scanning technology improves in leaps, especially in ink quality and image cleanup. “This has been important because color content has become much more standard and widespread,” DOE’s Freedman says.

A 1941 photo taken for a Farm Security Administration project shows migrant workers on a break in Belle Glade, Fla. Source: Library of Congress

“It is amazing how vibrant the colors are now,” Wharrie adds. In the 1940s and earlier, federal workers often wrote in pencil, and lead fades with time. The new scanning software can take something faded, make it readable and bring it back to life, he says.

“Also, the huge speed improvement in the computers coordinating the scanned images makes scan time quicker and file manipulation much more responsive,” Freedman says.

But file storage and communication capability has changed the most.

“It is now much easier for organizations to store and communicate gigabytes of converted data and thousands of files, which has changed the way converted electronic files are utilized,” Freedman says