For NOAA and the NWS, Big Data Is Saving Lives

Predicting natural disasters in time to notify citizens in danger comes down to data. The process is complicated, the measurables are vague and the reaction from possible victims is sometimes slow. In short, it’s a difficult process that technology could help solve.

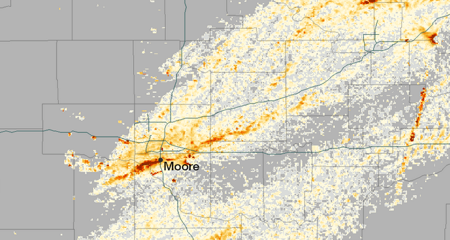

The devastating tornado in Moore, Okla., serves as a reminder that data, if collected and analyzed properly, can save lives. The process can be broken down into three steps: data collection, data analysis and data distribution. It’s not unlike other Big Data initiatives that aim to refine advertising campaigns or optimize data-center usage. The difference, of course, is that lives are on the line.

The Calm Before the Storm

Meteorologists collect a lot of data from many different sources. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Storm Prediction Center has excellent resources for anyone interested in learning about tornadoes. Here is a look at their overview of tornado prediction:

When predicting severe weather (including tornadoes) a day or two in advance, we look for the development of temperature and wind flow patterns in the atmosphere which can cause enough moisture, instability, lift, and wind shear for tornadic thunderstorms. Those are the four needed ingredients.

Real-time weather observations--from satellites, weather stations, balloon packages, airplanes, wind profilers and radar-derived winds--become more and more critical the sooner the thunderstorms are expected; and the models become less important. To figure out where the thunderstorms will form, we must do some hard, short-fuse detective work: Find out the location, strength and movement of the fronts, drylines, outflows, and other boundaries between air masses which tend to provide lift. Figure out the moisture and temperatures, both near ground and aloft, which will help storms form and stay alive in this situation. Find the wind structures in the atmosphere which can make a thunderstorm rotate as a supercell, then produce tornadoes. [Many supercells never spawn a tornado!] Make an educated guess where the most favorable combination of ingredients will be and when; then draw the areas and type the forecast.

As NOAA makes clear, the process is part science, part guesswork. Ideally, data would provide reliable indication of a tornado’s location and the time it would hit, but the technology is just not there yet.

Turning Data into Decisions

Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Environmental Visualization Laboratory

Atmospheric sciences professor Cliff Mass believes that the government needs as much one hundred times the computing it currently posseses to alert citizens hours rather than minutes before a disaster.

Improvements are being made in the data-collection phase, but the analysis stage is also advancing quickly. Historically, the United States has boasted the best storm-prediction technology in the world, but budget cuts are threatening funding for the National Weather Service (NWS). In a recent Washington Post article, lobbyist Kevin Kelly of Van Scoyoc Associates had this to say about the cuts, “Communities that experience a heightened risk of severe weather – which affects large portions of the nation in the spring and summer – face the chance of greater danger because the Weather Service will not be operating at 100 percent.”

With the appropriate budget, University of Washington atmospheric sciences professor Cliff Mass believes that citizen alerts could improve from about 13 minutes to more than three hours, but the National Weather Service will need “at least 10 to 100 times more [computing power] than they're getting.” The Hurricane Sandy relief bill has appropriated funds to address the need, and Mass is hopeful that the United States will soon be leading the way in weather prediction:

The National Weather Service will be acquiring a radically more powerful computer system during the next year, one that could allow the U.S. to regain leadership in numerical weather prediction. Used wisely, this new resource could result in substantial improvements in both global and regional weather predictions.

Using $24 million from the Superstorm Sandy Supplemental budget, the National Weather Service will be [able to acquire] two computers with a capacity 37 times greater than it uses today. We are talking about a transition from 70 teraflops right now (and 213 teraflops this summer) to 2600 teraflops in 2015.

Improving Notification Systems

302pm - LARGE VIOLENT TORNADO moving toward Moore and SW OKC. Take cover right NOW!!! Do not wait!! #okwx

— NWS Norman (@NWSNorman) May 20, 2013

Data collection and data analysis require incredibly complicated technology and huge investments. Notification systems, however, have benefitted from social media, mobile devices and increasing Internet speeds. As The New Yorker explains, the increased access to information is balanced by myriad platforms:

Today, in an age of media fragmentation, disseminating a message to everyone, in real time, is a serious challenge, and the federal government deserves praise for the Wireless Emergency Alert (W.E.A.) system, which it has rolled out over the past year. In emergencies, including extreme weather and man-made incidents, AMBER alerts, and Presidential alerts, the W.E.A. automatically sends a ninety-character text message to every smart phone within range of cellular towers in the designated target area. If the phone ringer is on, the system also generates a unique ringtone; if not, the message appears on the screen without a sound. Before something like a tornado, the text should arrive on most smart phones at about the same time that alert sirens, an old-fashioned but still effective communications device, go off.

Social media is also a key tool for communication, and local governments have become a source of information in weather emergencies. The National Weather Service is experimenting with hyperlocal Twitter accounts to disseminate information quickly. Coincidentally, the first pilot is in Norman, Okla., just minutes away from the devastation in Moore.

Weather predication and notification are steadily improving, but the advances can’t happen quickly enough. Do you have ideas on how the government can improve the process? Let us know in the Comments section.