Commerce, State Departments Take Steps to Combat Insider Security Threats

The forces behind the most notorious government data breaches in recent memory weren’t China, Russia, North Korea or Iran.

They were Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden — two insiders who used their positions and access to publicly release massive amounts of secret information.

In 2010, Manning, then an Army intelligence analyst with access to classified databases, released nearly three quarters of a million classified or sensitive documents to the open-information organization WikiLeaks. And in 2013, Snowden, then a contractor for the National Security Agency, shared thousands of classified documents with journalists.

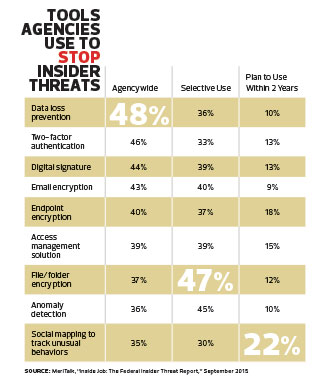

That both of these people worked for the government is not lost on federal IT leadership: Fifty-five percent of agencies now host a formal insider threat program, and 76 percent of IT managers say their agency is more focused on combating insider threats today than it was a year ago, according to a MeriTalk survey released last September.

A lot of agencies have begun different types of insider threat programs, says Patricia Larsen, co-director of the National Insider Threat Task Force, a program established by the Obama administration in the wake of the WikiLeaks release to help agencies prevent, deter and detect compromises of sensitive information by insiders.

“What we want to do now is bring all the information they collect together,” she says. “Things that used to be viewed as disparate information in their own stovepipes are now shared within agencies.”

Executive branch agencies have worked to meet the Insider Threat Task Force’s new minimum standards in areas such as employee training and user activity monitoring. Agencies also are rolling out tools and best practices to prevent insider-initiated leaks, but many agencies continue to report that insider threats are a persistent problem. What’s more, as with any cybersecurity initiative, the work is never complete.

Multiple Kinds of Insider Incidents

Forty-five percent of federal IT managers say their agencies have been the target of insider incidents in the past 12 months, according to the MeriTalk survey, and 29 percent of agencies lost data to insider incidents during that time span.

These numbers underscore the importance of insider threat detection and mitigation capabilities. During the Cold War, Larsen says, the average spy worked on a case for 11 years. “With today’s technology, we can’t afford to have someone spying for 11 years,” she says.

Clearly, data is easier to steal than ever before, with a $10, lipstick-size flash drive capable of storing 32 gigabytes of data. Digital records also make it more likely that well-meaning insiders might inadvertently expose data to hackers. In fact, a full 40 percent of the insider incidents reported in the MeriTalk survey were the result of unintentional actions — from failing to follow password protocols and falling for phishing scams to using unsecured connections to complete work tasks.

Agency IT managers hesitate to discuss specific sources of insider threats, but in conversations, many confirm that the new attention to insider threat programs has had an impact.

“We’re successful in our nascent insider threat program,” says Stephen Smith, insider threat program coordinator for the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, the security and law enforcement arm of the State Department. “We clear anomalous activity, or we take the referral a little further and look at whether the act was malicious and adjudicate it. The program has identified behaviors that cause us to take administrative and sometimes criminal action.”

Rod Turk, chief information security officer at the Commerce Department, says agencies must take an expansive view of what constitutes an insider threat. “We often think about insider threats as someone stealing confidential information,” he says. “There are other threats where people harm systems through availability — to take a system down so no one can use it — or change the information on a system so its integrity has been compromised.”

How to Handle the Threat

To effectively combat insider threats, agencies must move beyond a checklist approach to cybersecurity and instead work to strategically protect their most important IT assets, says Katell Thielemann, a research director for Gartner.

“A focus on insider threats attempts to shift risk management, forcing agencies to think about their mission, what level of risk they can accept and what controls can be put in place,” Thielemann says. “For agencies, it comes down to, ‘What are the crown jewels that I really need to protect?’”

Agencies must maintain a delicate balance when protecting against insider threats, adds Robert Westervelt, a research manager in IDC’s security products group. While IT managers need to put security controls in place, those controls must not be so restrictive that they incentivize employees to bypass them for convenience, he says.

“If you get too restrictive, shadow IT pops up,” Westervelt says. “That could be something as simple as an employee bringing in a cellphone and using it as a mobile hotspot to bypass the organization’s network, which could introduce a lot of different threats.”

Common tools for preventing and detecting insider threats include privileged account credentials, tamper-proof auditing programs and continuous monitoring tools that track employee behavior. Essentially, agencies must restrict access to sensitive data, track who accesses it, and pinpoint and investigate anomalous behavior.

Many agencies currently lack these capabilities. According to the MeriTalk survey, 45 percent of agencies cannot immediately tell if a document has been inappropriately shared; 42 percent cannot tell how a document was shared; and 34 percent cannot tell what data has been lost. Additionally, federal IT managers estimate that 43 percent of data repositories have not been classified into groups such as sensitive, not sensitive or critical.

At Commerce, the IT team uses a security information management tool and continuous monitoring to identify potential insider threats, Turk says. “We’re interested in anomalous behaviors from individuals with elevated privileges. If you see a large amount of classified information downloaded at 2 a.m. on a Saturday, then you know something is wrong.”

At State, the team actively monitors its users and audits classified networks, but Smith says he is reluctant to talk about specific solutions the agency uses. Looking forward, however, he expects that Big Data solutions will help detect insider threats.

“Government can benefit from Big Data to become more responsive,” Smith says. “It doesn’t take much time to exfiltrate sensitive information. We have to be as preventative as possible and mitigate insider threat attacks in a timely fashion.”

Increased Training

Whatever the final approach, it must involve both technology and people. Only 40 percent of federal IT managers think that security technologies are the best way to prevent insider threats, according to the MeriTalk survey. Another 40 percent say that end-user education and training is the most important prevention method, while 20 percent cite proper controls as the linchpin.

“This is both human and technical,” Westervelt says. “It’s not just security controls.”

While most agencies do provide employees with annual security training, what’s done varies. While 73 percent of federal IT managers say that they provide online security training each year, only 39 percent say they provide annual in-person training.

A lack of awareness could be partially responsible for the types of employee behaviors that lead to unintentional data breaches. Sixty-five percent of federal IT managers say it is common for employees and contractors to email documents to personal accounts, 51 percent say it is common for employees and contractors to fail to follow appropriate protocols, and 40 percent say that unauthorized employees access government information they shouldn’t at least weekly.

“Training is a huge piece of this,” Larsen says. “No technology tool in the world is going to be your silver bullet.”