Warning Signs About Election Security

The pandemic caused many states to reschedule their primaries, creating more points at which security decisions have to be made.

“You want an environment where everyone is thoroughly trained and familiar with the process. Uncertainty causes challenges,” says Hale.

Technical issues that occurred prior to the pandemic also sent up red flags for those concerned with election security, signs of what could be expected for the general election season.

Early on, an election app designed to allow precinct leaders to register voters’ choices failed spectacularly; it wasn’t well tested in advance, and volunteers received inadequate training.

Ironically, security measures added to the problems; those included a last-minute security patch as well as multifactor authentication that required smartphone use in locations where phones weren’t permitted.

“This just set election innovation back so far,” says Rita Reynolds, CTO of the National Association of Counties. “You have to do testing, you have to do pilots, you have to do a soft rollout.”

States also ran into capacity issues early on. In some jurisdictions, limitations on network capacity prevented election officials from looking up voter information and led poll workers to have to print out paper ballots.

In others, bandwidth problems prevented some voters from accessing online tools that helped them find their polling locations; in one location, this was compounded by a volunteer who unwittingly redirected voters to a partisan site for information.

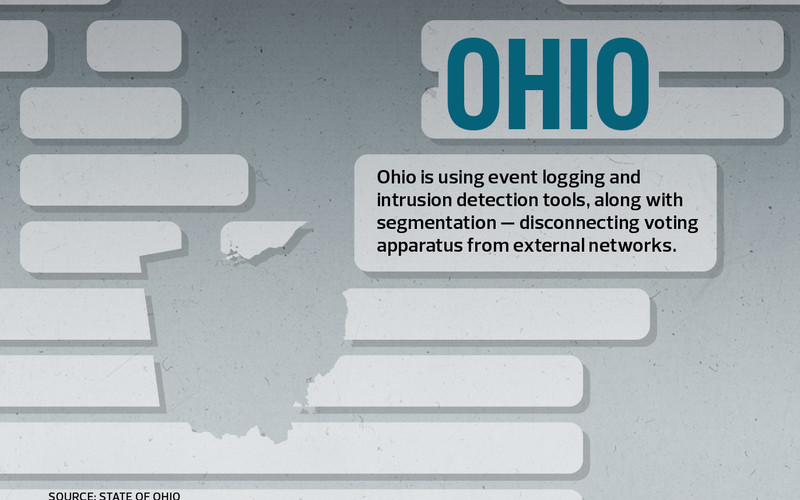

LEARN MORE: Explore this infographic on election security processes.

Firewalls Can Help Slow Disruptions

To counter this technological uncertainty, “the most important thing is to have backup procedures in place as part of the resiliency plan,” says Elizabeth Howard, counsel in the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law.

“You need a system that would minimize any interruption to voting, which includes having sufficient paper ballots present for everyone to cast their votes,” she adds.